I was diagnosed with endometriosis while having surgery at age 25. I had been to see many doctors and was prescribed lots of different drugs and treatments, including painkillers, pills, hormone treatments and surgery. I’ve had drastic improvement with Sandra’s plan.

Manage endometriosis successfully and be pain free

- Early warning signs

- Presentation and Diagnosis

- Origin of Endometriosis

- Development and Progression of Endometriosis

- Additional sources of inflammation

- Disrupting the feedback loops, reducing PEG2 and supportive anti-oxidants are effective treatments for endometriosis

- Associations

- Contraindications for Endometriosis

- My approach to Managing Endometriosis – A pain-free Life is Possible

- Takeaways

Endometriosis is a complex and often misunderstood condition that affects millions of women worldwide. It occurs when the tissue similar to the lining of the uterus, known as the endometrium, grows outside the uterus. This misplaced tissue can be found in various areas of the body, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic lining, and even distant organs like the bladder or intestines.

Unlike the normal endometrial tissue that sheds during menstruation, the displaced endometrial tissue has no means of exit from the body. This can lead to the formation of painful adhesions, scar tissue, and the development of cysts, causing a range of symptoms and complications.

Early warning signs

It is often difficult to evaluate endometriosis by physical examination and clinical history review. The warning signs include:

- The first sign is unbearable period pain from the very first period. The typical symptoms in teenage girls include:

- Avoidance of exercise during the period, particularly if due to excessive pain or heavy flow

- Increased anxiety, depression and/or fatigue in relation to pain

- Nausea with pelvic pain, especially if it is non-cyclic pain

- Period pain or pelvic pain so severe it interferes with school/socialising/work/daily activities

- Gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhoea/constipation particularly around the time of the period and in relation to period pain

- Pelvic pain/period pain that does not respond to treatment with painkillers or hormonal treatments like the pill

- Heavy or irregular periods

- Pain during intercourse

- Digestive problems – the endo belly – pronounced bloating or swelling of the abdomen, which can often be uncomfortable or painful, often accompanied by a feeling of ‘fullness’ in the abdomen. This bloating may occur at certain points of the menstrual cycle or randomly at other points of the month.

One of the common symptoms of endometriosis is very painful bowel movements specially during the menstrual cycle. But the bowel symptoms are not only limited to painful defecation, but it can include the following:

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Bloating

- Rectal bleeding

- Nausea and vomiting

- Infertility and furthermore, studies on IVF have shown that women with endometriosis have higher rates of pregnancy loss, complication of preterm delivery, pre-eclampsia and infants small for gestational age.

Presentation and Diagnosis

Endometriosis most often occurs on or around reproductive organs in the pelvis or abdomen, including:

- Fallopian tubes

- Ligaments around the uterus (uterosacral ligaments)

- Lining of the pelvic cavity

- Ovaries

- Outside surface of the uterus

- Space between the uterus and the rectum or bladder

More rarely, it can also grow on and around the:

- Bladder

- Cervix

- Intestines

- Rectum

- Stomach (abdomen)

- Vagina or vulva

Endometrial tissue growing in these areas does not shed during a menstrual cycle like healthy endometrial tissue inside the uterus does. The buildup of abnormal tissue outside the uterus can lead to inflammation, scarring and painful cysts. It can also lead to adhesions – the buildup of fibrous tissues between reproductive organs that causes them to “stick” together.

Diagnosing endometriosis requires a combination of medical history, physical examination, and imaging tests such as ultrasound or MRI. A definitive diagnosis can only be made through laparoscopy, a surgical procedure in which a thin tube with a camera is inserted through a small incision in the abdomen to view the pelvic organs and remove any abnormal tissue for biopsy.

Some of the procedures to diagnose a suspected case of endometriosis are

- Laparoscopy: It is a surgical process. A camera is utilized to have a look into the abdominal cavity and estimate the severity of the condition. It visualizes the externally visible lesions. If the lesions are not visible, a biopsy can be drawn. This process of diagnosis also allows for surgical treatment through laparoscopy. 6 to 13 percent of women have shown the invisible lesions of endometriosis in the biopsy.

- Ultrasound: a pelvic ultrasound detects the larger endometriotic cysts as in ovaries called endometriomas. However, it has no role in diagnosing smaller implants. Vaginal ultrasound is used in detecting deeper endometriomas and before operating on them. This is one of the most easily accessible, inexpensive and required no preparation.

- Magnetic resonance imaging: it is a noninvasive technique. But due to its limited availability and cost, it is not widely recommended. But it precisely and accurately diagnoses smaller lesions.

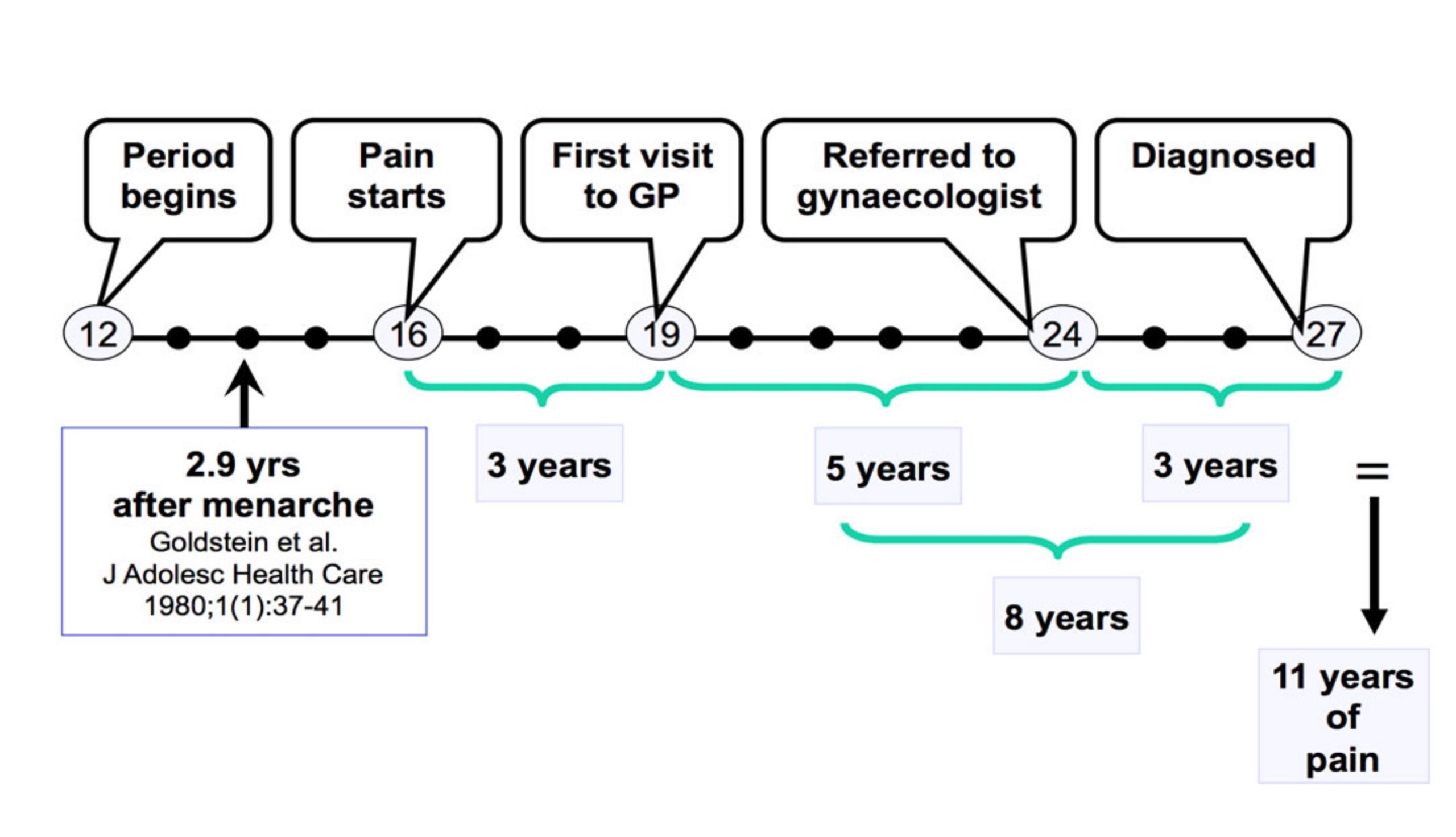

Diagnosis delays – it’s something else

A US survey found that 75.2% of endometriosis sufferers were initially misdiagnosed as either having another physical disorder or mental health issue and many doctors choose to go down the route of symptom management like pain relief or hormonal medication without any formal diagnosis.

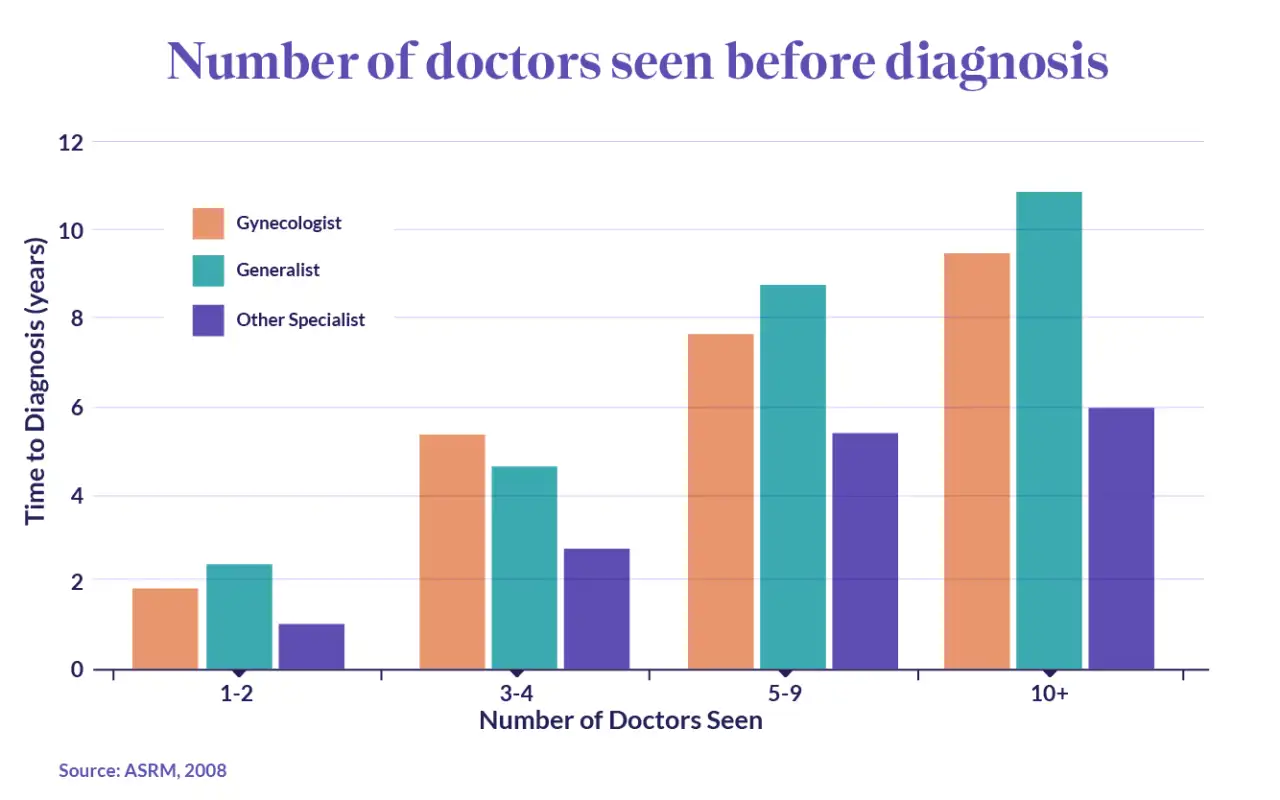

For those that insist on finding an answer to their debilitating symptoms, pursuing the issue takes time and patience. A US study found that 23.5% of endometriosis patients see 5 or more physicians before receiving a diagnosis. And the more physicians patients saw, the longer the diagnostic delay. Those that only saw 1 to 2 doctors received a diagnosis in 1 to 2 years, while this increased to 7 to 8 years for those that saw 5 to 9 physicians.

Why is there such a delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Studies have found that women are less likely to feel listened to and taken seriously, and are assumed to have a higher pain threshold. One of the main side effects of endometriosis is chronic pain, and because endometriosis patients don’t receive a definitive diagnosis until they’ve had laparoscopic surgery, not having their pain believed can be particularly harmful.

Activists have used the term ‘gender health gap’ to bring together evidence that would suggest that your gender has a bearing on your experience with doctors and the healthcare you receive. Studies that point out that women are 25% less likely than men to receive pain relief have been used to back up the notion of gender bias in medicine.

In a study published in 2018, entitled “Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”, researchers concluded that pain experienced by women was often described as medically inexplicable, as there was often no visible cause for their pain. As a result, healthcare professionals often attributed the pain to a psychological rather than physical cause. This was due to the absence of any visible or diagnostic evidence of illness.

Studies have found that in addition to medical professionals assuming that women have higher pain thresholds, there is also an assumption that they are more emotionally unstable. Research published in 2001 found that when women came to their doctors with legitimate concerns of chronic pain, they were more likely to be described as “emotional”, and their pain to be “psychogenic”, and “not real” by their medical expert. This is especially harmful for endometriosis patients who already face long diagnosis waiting periods and may not feel like they’re listened to.

The gender health gap, especially as it relates to endometriosis, has historical roots in medical practice. Endometriosis.org explains that pain associated with endometriosis is often dismissed because “‘women’s problems’ perplexed nineteenth-century doctors, who saw them as indicative of unstable and delicate psychological constitutions. Even though attitudes […] have improved during the twentieth century, some of the old beliefs still linger unconsciously, and affect the medical profession’s attitudes towards complaints including period pain.”

In 2014, Brigham and Women’s hospital in the U.S. said that medical developments that look into the way conditions are treated and diagnosed “routinely fail to consider the crucial impact of sex and gender. This happens in the earliest stages of research when females are excluded from animal and human studies or the sex of the animals isn’t stated in the published results.” This would suggest that in order to tackle the gender health gap and improve medical understanding of conditions like endometriosis, medical research that includes and prioritizes the experiences of people who identify as women need to take place in higher numbers.

The lack of medical research on endometriosis leads to less medical education on the disease, and can result in serious delays in the period of time it takes to receive an endometriosis diagnosis and how much your doctors understand about the condition.

Misdiagnoses

Many women with endometriosis who have gastrointestinal symptoms are often misdiagnosed as

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Crohn’s disease

- Appendicitis

If symptoms are cyclical in nature, it’s a sign indicating endometriosis. Some women may have symptoms throughout the cycle in chronic cases but the symptoms do aggravate during menstruation

Origin of Endometriosis

The origin of endometriosis is still not well defined. Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the development of endometriosis and Dr David Redwine has proposed the most viable theory – Mulleriosis – that appears to cover all the salient features of endometriosis. His theory favours a genetically-driven embryonic origin of endometriosis. Müllerian tissue is tissue in a female embryo that eventually develops into the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and the upper part of the vagina. Mulleriosis indicates a problem of differentiation and migration of any Mullerian tissue during the formation of the embryo which results in patches of this tissue being laid down in abnormal locations in the pelvis or elsewhere in the body. Later in life, these misplaced patches of tissue develop into endometriosis when they are exposed to oestrogen.

To support his theory, Dr Redwine described a case of fingertip endometriosis, where surgical excision brought complete relief. He posits that that’s because the entire tract of Mulleriotic tissue that had been laid down in the dermis or nail bed had been removed by excision.

Via Dr David Redwine:

The cause of endometriosis is a subject of continued debate. My best guess is that it is a disease that the woman is born with because of a process called embryologically patterned metaplasia. At the moment of conception, a woman is dealt three cards.

- The first card is that she will have endometriosis.

- The second card is where in her body the disease will be.

- The third card is how biologically active the disease will be in each area.

And depending on these various cards, which can be quite different from patient to patient, endometriosis, or areas that will become endometriosis, are laid down in the woman’s pelvis or elsewhere in the body during foetal formation. When oestrogen production begins at puberty, the tracts of tissue that were laid down can become painful and can begin to change into endometriosis. Men can also develop endometriosis for somewhat the same reasons.

Excision is the only cure

Going by Dr Redwine’s theory, excision of the lesions is the only cure for endometriosis, however it needs to be done by a surgeon who is specialised at removing the lesions ‘from the root’ otherwise they will grow back. The recurrence of endometriosis after ovarian endometrioma excision has been evaluated at 24, 36, 60, and 120 months as 5.8%, 8.7%, 15.5% and 37.6% respectively.

Development and Progression of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is driven by oestrogen that may come from the ovaries or from within the lesions themselves. Women with endometriosis tend to to have higher ovarian production of oestrogen and this combined with lesional oestrogen can result in high levels that make symptoms worse.

The central driver connecting oestrogen to symptoms is the high production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 is a regulator that makes the environment inside the body more favourable for endometriosis to develop and progress by affecting various cellular activities and immune responses. Specifically, it:

- Promotes cell growth (cell proliferation): PGE2 makes cells multiply faster, which can contribute to the growth of endometrial tissue where it shouldn’t be.

- Prevents programmed cell death (antiapoptosis): Normally, cells have a built-in process of dying when they are damaged or not needed, called apoptosis. PGE2 stops this process, allowing potentially harmful cells to survive longer.

- Weakens the immune system’s response (immune suppression): It hinders the body’s immune system from effectively responding to these abnormal cells.

- Stimulates the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis): PGE2 encourages the growth of new blood vessels, which can supply more nutrients to the endometrial tissue growing outside the uterus, allowing it to grow more.

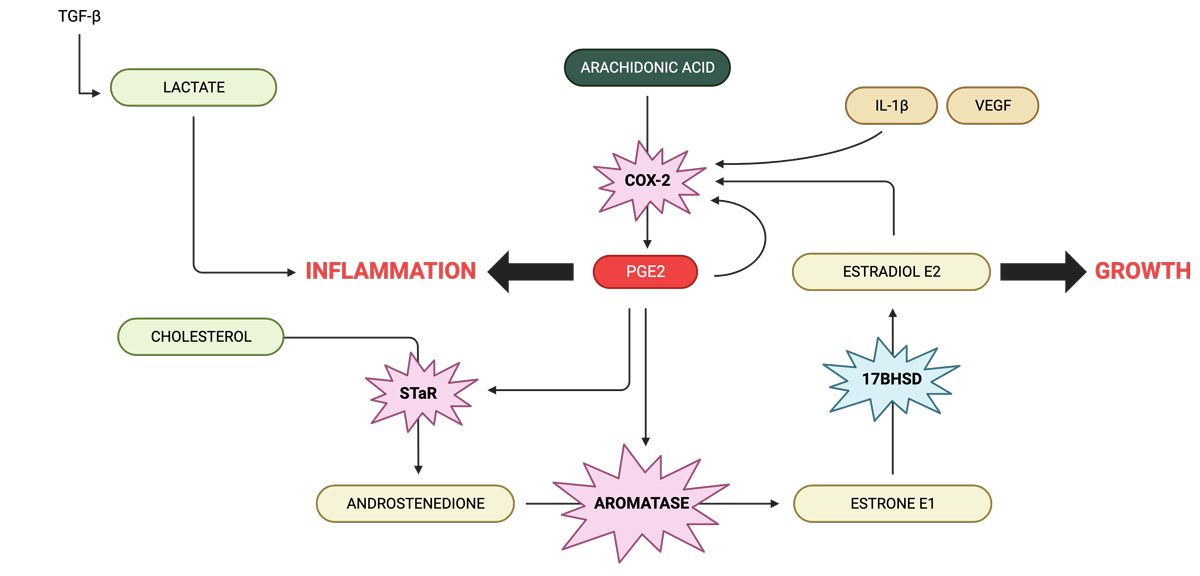

Feedback loop between oestrogen and PGE2 promotes growth and inflammation

Two basic pathologic processes, namely growth and inflammation, are responsible for chronic pelvic pain and infertility, which are the primary devastating symptoms of endometriosis. Estrogen enhances the growth and invasion of endometriotic tissue, whereas PGE2 and cytokines mediate pain, inflammation and infertility.

Estradiol (E2) is produced locally in endometriotic tissue. The precursor, androstenedione of ovarian, adrenal or local origin becomes converted to estrone (E1) that is in turn reduced to E2 in endometriotic implants.

Endometriotic tissue is capable of synthesising androstenedione from cholesterol via the activity of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and other steroidogenic enzymes also present in this tissue. E2 directly induces cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2), which gives rise to elevated concentrations of PGE2 in endometriosis. The cytokine Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and PGE2 itself are also potent inducers of COX-2 in uterine cells. PGE2, in turn, is the most potent known stimulator of StAR and aromatase in endometriotic cells. This establishes a positive feedback loop in favour of continuous oestrogen and PG formation in endometriosis.

Feeding into this loop is arachidonic acid which is synthesised from omega-6 fats commonly found in foods. COX-2 converts arachidonic acid to to PEG2 which directly increases COX-2, creating another feedback loop.

PEG2 increases the rate of the enzyme aromatase, increasing E1, and because the enzyme 17β-HSD is low in edometriotic tissue, this then increases the production of E2.

Women with endometriosis produce more lactate which stimulates an environment that promotes invasion of endometrial cells into the peritoneum so that they form lesions.

PGE2 prevents the macrophages of the immune to do a clean up job

Abnormal hormone production by endometriotic lesions is a significant factor that helps endometriotic tissues survive and grow. However alongside this is a critical issue in immune system dysfunction, particularly the reduced ability of immune cells to consume and remove unwanted materials, a process known as phagocytosis. This dysfunction is largely due to macrophages, a type of immune cell responsible for cleaning up debris, not working properly.

In cases of endometriosis, these macrophages are attracted to the peritoneal cavity, an area inside the abdomen, because of inflammation. Ideally, they should remove abnormal endometrial tissue that is present in the peritoneal cavity. However, they often fail to do this effectively in endometriosis, allowing the endometriotic tissue to grow.

The way macrophages function involves two main methods. Firstly, they produce zinc-based enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to break down the surrounding material of foreign entities. Secondly, they use scavenger receptors (CD36) to enhance the uptake and destruction of cell debris. In endometriosis, however, the function of these macrophages is impaired. In the presence of a high concentration of PGE2, the expression of MMP-9 and CD36 is suppressed. This significantly inhibits the phagocytic ability of macrophages. As a result, the endometrial tissues proliferate in the peritoneal cavity, maintaining and progressing endometriosis.

In essence, the development of endometriosis is not just about the abnormal production of hormones by the lesions but also involves significant dysfunction in the immune system, especially in macrophages. This dysfunction is characterised by a reduced capacity to remove unwanted materials and impaired production of important enzymes and receptors, influenced by PGE2 in the peritoneal fluid.

PGE2 is the likely master of endometriosis

In women with endometriosis, there are two self-reinforcing cycles that keep the levels of PGE2 high in the peritoneal fluid.

- PGE2 – COX-2 – PGE2 pathway in macrophages: In peritoneal macrophages (immune cells in the abdominal cavity), PGE2 increases the activity of an enzyme called COX-2, leading to more production of PGE2.

- PGE2 – Estrogen – COX-2 – PGE2 pathway in lesions: In ectopic endometriotic lesions (abnormal tissue growths), PGE2 boosts estrogen production, which then increases COX-2 activity, resulting in more PGE2.

- High PGE2 Levels then lead to:

- Abnormal steroid production: PGE2 leads to unusual production of steroidogenic proteins, like StAR and aromatase. This results in excess production of estradiol, a key hormone for endometrial tissue survival.

- Stimulation of growth factors: The estradiol produced by ectopic tissues increases growth factors (like VEGF and FGF), promoting cell growth (proliferation) and new blood vessel formation (angiogenesis).

- Direct impact on cell growth: PGE2 directly causes endometriotic and blood vessel cell growth through increased levels of FGF and VEGF.

- Reduced macrophage function: PGE2 inhibits the expression of MMP-9 and CD36 in macrophages. This diminishes their ability to clean up debris, aiding the survival and growth of endometriotic lesions.

In essence, elevated PGE2 in the peritoneal fluid maintains a cycle that encourages the development and persistence of endometriosis by influencing increased hormone production and cell proliferation, and immune cell dysfunction.

Additional sources of inflammation

Interactions with gut bacteria, blood debris, iron overload, anti-oxidant deficiencies, increased nitrites/nitrates and gene expression of oestrogen metabolism also play a part in maintaining endometriosis.

- Bacterial contamination from the gut creates more inflammation and make endometriosis worse via PGE2

Researchers have found that some of the gut microbes linked to bowel problems also feature prominently in endometriosis. When they treated the mice with the broad-spectrum antibiotic metronidazole, the lesions became smaller. Inflammation also was reduced.

Additional research found that the menstrual blood was highly contaminated with E. coli and that the endometrial samples were colonised with other bacteria. The concentration of bacterial toxins – endotoxin – was four to six times higher in the menstrual blood of women with endometriosis compared to those without endometriosis. Treatment with GnRH agonist further worsened the colonisation of the uterus by bacteria potentially leading to endometriosis.

There appears to be an additive effect between estradiol and endotoxin on the proliferation endometrial cells and that an immune-endocrine cross-talk between oestrogen and endotoxin in the pelvic ecosystem creates an inflammatory environment leading to growth of endometriosis. The connection appears to be PGE2: PGE2 is increased by endotoxin, and PGE2 also stimulates increased growth of bacteria that produce endotoxin.

Further, endotoxin promotes the polarisation of macrophages from M1 to M2, increasing the progression of endometriosis.

Therefore, as well as considering oestrogen/hormone biotransformation in endometriosis, we should also be looking at the gut and vaginal microbiomes for endotoxin-producing bacteria, modulation of the gut ‘oestrobolome’ (bacterial recycling of oestrogen in the gut), endotoxin clearance by the liver and liver support. - Blood debris causes oxidative stress which promotes inflammation

It is now widely accepted that oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants, may be implicated in the pathophysiology of endometriosis causing a general inflammatory response in the peritoneal cavity. ROS are intermediaries produced by normal oxygen metabolism and are inflammatory mediators known to modulate cell proliferation and to have negative effects.

The body’s complex antioxidant system is influenced by dietary intake of non-enzymatic antioxidants such as manganese, copper, selenium and zinc, beta-carotenes, vitamin C, vitamin E, taurine, hypotaurine, and B vitamins. On the other hand, the body produces several antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, super- oxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, and molecules like glutathione and NADH. Glutathione is produced by the cell and plays a crucial role in maintaining the normal balance between oxidation and antioxidation. NADH is considered as an antioxidant in biological systems due to its high reactivity with some free radicals, its high intracellular concentrations and the fact that it has the highest reduction power of all biologically active compounds. When the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defence is disrupted, higher levels of ROS are generated and oxidative stress may occur, leading to harmful effects. Oxidative stress is implicated as a major factor involved in the pathophysiology of endometriosis.

Macrophages, red blood cells, and apoptotic endometrial tissue are well known inducers of oxidative stress; therefore, peritoneal production of ROS may be involved in endometriosis. Indeed, activated macrophages play an important role in the degradation of red blood cells that release prooxidant and proinflammatory factors such as heme and iron, implicated in the formation of inflammatory ROS. - Inflammation from excess iron

Higher levels of iron, ferritin, and haemoglobin have been found in the peritoneal fluid of affected women than controls. The stroma of endometriotic lesions and peritoneum also revealed the presence of iron conglomerates. Iron overload acts as a catalyst to generate a wide range of ROS, inducing injury to cells.

Oxidative stress destroys tissue which produces adhesions. Iron-binding protein haemoglobin has been identified as one of the factors potentially leading to adhesion formation.

ROS production by iron overload induces an increase of NF-kappa B in peritoneal macrophages, leading to pro-inflammatory, growth, and angiogenic factors.

Iron, heme, and hemoglobin accumulation leads to oxidative stress causing DNA hypermethylation and histone modifications. DNA hypermethylation is linked to defective endometrium development in endometriosis.

Treatment with an iron chelator could thus be beneficial in endometriosis, to prevent iron overload in the pelvic cavity, thereby diminishing its deleterious effect. - Inflammation from deficiency of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD): SOD is an important antioxidant system. It catalyses the dismutation of superoxide into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen. SOD shows a decreased activity in the plasma of women with endometriosis, suggesting a decreased antioxidant capacity. SOD requires manganese as a cofactor (see the section on interventions).

- Inflammation from deficiency of Glutathione Peroxidase:

Glutathione peroxidase is an antioxidant enzyme class with the capacity to scavenge free radicals. This is in turn helps to prevent lipid peroxidation and maintain intracellular homeostasis as well as redox balance. Glutathione peroxidase is localised in the glandular epithelium of normal human endometrium and reaches a maximum level in the late proliferative and early secretory phases of the menstrual cycle.

A study on endometriosis-associated infertility demonstrated a lower mean activity of glutathione peroxidase and increased lipid peroxidation in infertile women with endometriosis compared to women without this disease. This suggests that low level of antioxidant enzymes in the peritoneal fluid plays an integral role in the development of endometrial pathology. Furthermore, in women with endometriosis, abnormal expression of glutathione peroxidase in eutopic and ectopic endometrium has been reported. Overall, this aberrant change in antioxidant enzyme level can be one of the many contributors of the oxidative damage seen in endometriosis (see the section on interventions for approaches to manage glutathione levels). - Inflammation from Nitrates and Nitrites

The concentrations of nitrates and nitrites are higher in endometriosis and are higher in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis, especially those with intestinal involvement. The higher concentration of nitrates probably derives from the augmented nitric oxide (NO) activity of the peritoneal macrophages and a higher activity of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS 2). A significant correlation between pelvic pain symptom scores and peritoneal protein oxidative stress markers was observed in women with endometriosis.

This suggests that NO plays a role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, especially in the most aggressive form with intestinal involvement. Additionally, peritoneal macrophages in endometriosis produce more NO in vitro after endotoxin treatment.

NO may contribute to painful symptoms, and reduction of blood nitric oxide levels is associated with clinical improvement of the chronic pelvic pain related to endometriosis.

NO activates COX-2, which in turn increases the levels of PGE2, thereby causing the levels of aromatase, the enzyme necessary for estrogen production. The resultant estrogen elevation stimulates further eNOS gene expression in a positive feedback loop (see the section on interventions for approaches to manage nitric oxide production). - Gene Expression of Oxidative Metabolism of Estrogens – methylation, COMT and liver detoxification

Increased expression of CYP1A1, CYP3A7, and COMT was observed in endometriosis. Expression of SULT1E1, SULT2B1, UGT2B7, NQO1, and GSTP1 was decreased. These findings exhibit a disturbed balance between phase I and II liver metabolising enzymes in endometriosis, leading to excessive hydroxy-estrogen and altered ROS formation, and stimulation of ectopic endometrium proliferation.

This model suggests increased 2-hydroxylation and 16α-hydroxylation and high 4 hydroxylation of estrogens together with high methylation, lower sulfatation and glucuronidation of CEs and 16α-OH-estrogens in endometriosis. This imbalance between phase I and II metabolic enzymes can result in excessive 2- and 16α-OH-estrogen and corresponding oestrogen quinone formation. The first could be involved in maintaining strong oestrogen agonistic activity in endometriotic tissue, while the second might be a source of excessive ROS generation. Moreover, altered NQO1 isoform distribution could result in impaired detoxification of toxic quinone oestrogens and may contribute to over enhanced ROS production in endometriosis. Apart from E2, 4-OH-, 16α-OH-estrogens and ROS can also be responsible for excessive growth of ectopic endometrium in ovarian endometriosis. ROS scavengers, or even antioxidant nutrients, might, therefore, influence the proliferation of ovarian endometriotic cells.

Disrupting the feedback loops, reducing PEG2 and supportive anti-oxidants are effective treatments for endometriosis

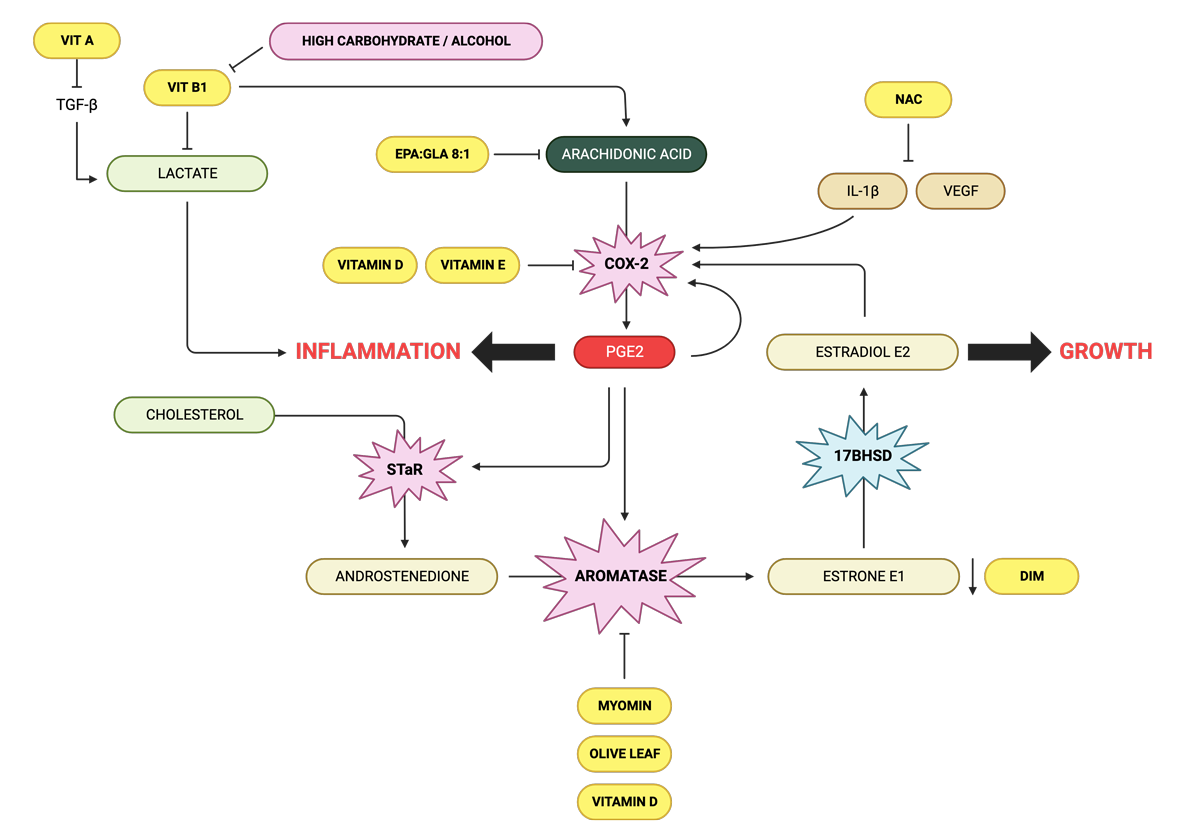

Understanding the biochemical pathways involved in the maintenance and progression pf endometriosis provides targets for interventions to reduce and manage inflammation and lesion growth.

Arachidonic acid inhibitors

- EPA:GLA ratio of 8:1

Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are biologically active fats which the body requires to support several important functions from blood clotting to inflammation; differentiating them from other fats which are either stored or used for energy. EFAs are deemed ‘essential’ because humans and other animals cannot produce them; meaning that they must be consumed from food.

The two types of fatty acids which are essential to the body are omega-3 (ALA) and omega-6 (LA). Other fatty acids such as EPA, DHA and GLA are considered ‘conditionally essential’ as they may become essential under certain developmental or disease conditions.

Arachidonic acid, derived from LA is found in meat, eggs and dairy, and is needed to support muscle growth, brain development and a healthy nervous system. However, we only require very small amounts of this fatty acid and when consumed in excess, it can promote inflammation.

Human studies have revealed that when EPA is introduced in a balanced ratio to GLA, elevations in serum arachidonic acid are prevented leading to a reduction in levels of pro-inflammatory PGE2. This conversion requires adequate zinc, magnesium and vitamin B6 as cofactors.

The ideal ratio of EPA to GLA to suppress arachidonic acid is 8:1 and should be combined with the cofactors.

- Quercetin

Quercetin is found many fruits and vegetables including citrus fruits, apples, onions and strawberries, and is known to reduce inflammation. It does this by interfering with the production of arachidonic acid. Specifically, quercetin stops the creation of inflammatory mediators like PGE2 and leukotrienes. These mediators are not only involved in causing inflammation but also play a role in controlling how the uterus contracts. Quercetin has been shown to significantly reduce endometrial lesions.

COX-2 inhibitors

- Berberine shows dose dependent PGE2 inhibitory activity via suppressing the COX-2 expression.

- Vitamin D is a COX-2 inhibitor and vitamin D levels have been shown to be low in women with endometriosis.

- Vitamin E exerts anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting prostaglandin E2 production from arachidonic acid through a decline in COX-2 activity. In a double-blind study of women with pelvic pain presumed to be due to endometriosis, supplementation with vitamin E (1,200 IU per day) and vitamin C (1,000 mg per day) for eight weeks resulted in a significant improvement of pain in 43% of women, whereas none of the women receiving a placebo reported pain relief. Vitamin E and C combined reduced pain and inflammation in women with endometriosis in another study.

- L-arginine boosts nitric oxide production. A lack of nitric oxide activates COX-2 and subsequently, prostaglandin PGE2 is increased and causes aromatase levels to rise as well. The resultant oestrogen increase stimulates further inflammation in a positive feedback loop.

IL-1, VEGF and oxidative stress inhibitors

- NAC (N-acetyl-cysteine) reduces the oxidative stress and inflammation play a key role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis-related pain. The release of cysteine from NAC, a precursor of reduced glutathione, allows the molecule to perform an indirect antioxidant action, with the removal of ROS leading to the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha), VEGF, and metalloproteinases, whose concentration is increased in the peritoneum of women with endometriosis. Supplementation of NAC at 600 mg, 3 tablets/day for 3 consecutive days of the week for 3 months significantly reduced the incidence of chronic pelvic pain, pain with sex, use of painkillers, size of the endometriomas and the serum levels of CA-125. Among the 52 women with reproductive desire, 39 successfully achieved pregnancy within 6 months of starting therapy

- IP6 is an iron scavenger. Iron overload from internal bleeding causes increased proliferation of endometrial lesions and progression of the disease. By decreasing levels of iron, the levels of oxidative stress resulting from free iron in the peritoneal cavity can also be controlled.

- Lactoferrin is an iron metabolism regulator. Heavy bleeding leads to iron loss and anaemia, but taking iron can feed bacteria and cause more pain and inflammation. Lactoferrin can regulate iron metabolism without these concerns.

Lactate inhibitors

- Vitamin B1 (thiamine) can reduce excess lactate made from malfunctioning mitochondria which upregulates PEG2, and reduce the pain of endometriosis. A deficiency of thiamine has been found to promote endometriosis. Dr Derrick Lonsdale prefers Lipothiamine (TTFD), although Benfotiamine has been found to reduce arachidonic acid in macrophages.

StaR inhibitor

- Melatonin, which induces sleep, has been shown to inhibit the conversion of cholesterol to androstenedione, thereby decreasing the amount available to be converted to oestradiol. A Phase 2 randomised clinical trial involving 40 women with endometriosis, ages 18 to 45 showed that melatonin treatment significantly reduced endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain and improved sleep quality without having to use a painkiller. Digital devices such as laptops, smartphones, and tablets generate blue light that can inhibit the natural production of melatonin.

Aromatase inhibitors

- Vitamin D reduces the expression of aromatase, decreasing oestrogen production.

- DIM is a compound found in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli and cauliflower. It works by inhibiting the activity of aromatase and balancing the levels of oestrogen in the body.

- Myomin – this is a natural supplement that has gained attention for its potential benefits in managing endometriosis. It is made from a blend of Chinese herbs, including Chinese yam, black cohosh, and polygonum. Myomin works by helping to regulate oestrogen metabolism in the body. It supports the liver’s ability to metabolise oestrogen, which can help to reduce overall oestrogen levels. By doing so, it may help to reduce inflammation and pain associated with endometriosis, as reported anecdotally.

Reducing systemic oestradiol (from the ovaries, gut and adrenals)

- Vitamins B1 and B2 maintain oestrogen detoxification by the liver, and a deficiency can lead to excess estradiol. Alcohol and high carbohydrate diets increase the need for vitamin B1 and supplementation would be required.

- Calcium D-glucarate is a natural compound found in fruits and vegetables. It works by inhibiting the activity of beta-glucuronidase made by gut bacteria, an enzyme that helps to circulate oestrogen back into the body from the gut.

Associations

There has been extensive data over the past decades indicating endometriosis may be linked to select co-morbid conditions in some individuals with the disease as well, including but not limited to a low/modest association between certain pigmentary traits and melanoma; pain syndromes (interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome/inflammatory bowel disease, chronic headaches, chronic low back pain, vulvodynia, fibromyalgia, temporomandibular joint disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, etc.) as well as mood conditions (defined as depression and anxiety) and asthma; select infections and endocrine disorders; headaches and migraines; thyroid disease and others. Similarities in the clinical and epidemiological features of the associated disorders may be at the root of their co-morbidity, and further investigation is needed.

There is a very strong association with many autoimmune diseases and endometriosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis probably being the most prevalent, as well as lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, scleroderma and multiple sclerosis. 3 common gene fingerprints – known as haplotypes – are prevalent with women with endometriosis. One of these haplotypes accounts for about 90 percent of all autoimmune disease an includes celiac disease, which is why cutting out gluten can have a tremendous benefit symptomatically (see the section on interventions for dietary recommendations).

The other haplotypes are associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, autoimmune hepatitis and are antibody mediated. The antibodies can react to paternal antigens in pregnancy and can lead to pregnancy loss. This may be a cause of repeated miscarriages and multiple IVF failures, and may point to ‘silent endometriosis’ where endometriosis exists, but does not present with any of the common symptoms.

Endometriosis is often associated with Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) an irresistible urge to move the legs due to an unpleasant non-painful sensory disturbance, described in a variety of ways for example as crawling, creeping and pulling. RLS is associated with dopamine deficiency. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter which mediates multiple functions in the body and its deficiency is associated with

- low moods

- depression

- fatigue

- lack of motivation

- inability to experience pleasure

- insomnia

- trouble getting going in the morning

- mood swings

- forgetfulness

- memory loss

- inability to focus and concentrate

- inability to connect with others

- low libido

- sugar cravings

- caffeine cravings

- inability to handle stress

- inability to lose weight

Research shows that women with moderate to severe endometriosis have a higher than normal frequency of genes which show mutations – polymorphisms – in dopamine receptors – dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2). The presence of polymorphism 2 could cause a defect in a post-receptor signalling mechanism, resulting in a mild increase in serum prolactin levels. Prolactin has angiogenic activity which may promote implantation of ectopic endometriosis tissue.

Studies with the dopamine agonist – a drug that promote a dopamine response – quinagolide, have shown a 69.5% reduction in the size of the lesions, with 35% vanishing completely. By interfering with angiogenesis, enhancing fibrinolysis, and reducing inflammation, quinagolide reduces or eliminates peritoneal endometriotic lesions in women with endometriosis.

Women receiving Carbegoline – another dopamine agonist – experienced considerable pain relief, through the lowering of prolactin.

Pentoxifylline, which can act as a dopamine agonist, has also been shown to increase pregnancy rates in women with endometriosis.

The use of high doses of dopamine agonists may cause an increase in the number of receptors that can make the post-receptor signalling mechanism work properly with this compensation, despite the presence of the polymorphism.

Dopamine can be increased naturally with the use of the amino acid l-tyrosine.

Contraindications for Endometriosis

Women with endometriosis should not use the copper coil because its side effects include longer, heavier and more painful periods.

Studies analysing the impact of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopausal with endometriosis are conflicting, with some research showing that oestrogen therapy could reactivate endometriosis. A systematic review of the literature suggested that the malignant transformation of the ectopic endometriotic tissue is related to oestrogenic stimulation. Women who are suffering with hot flushes, night sweats, brain fog, weight gain, anxiety and fatigue can reverse all these symptoms within 6 weeks with the Menopause Core Nutrition Solution.

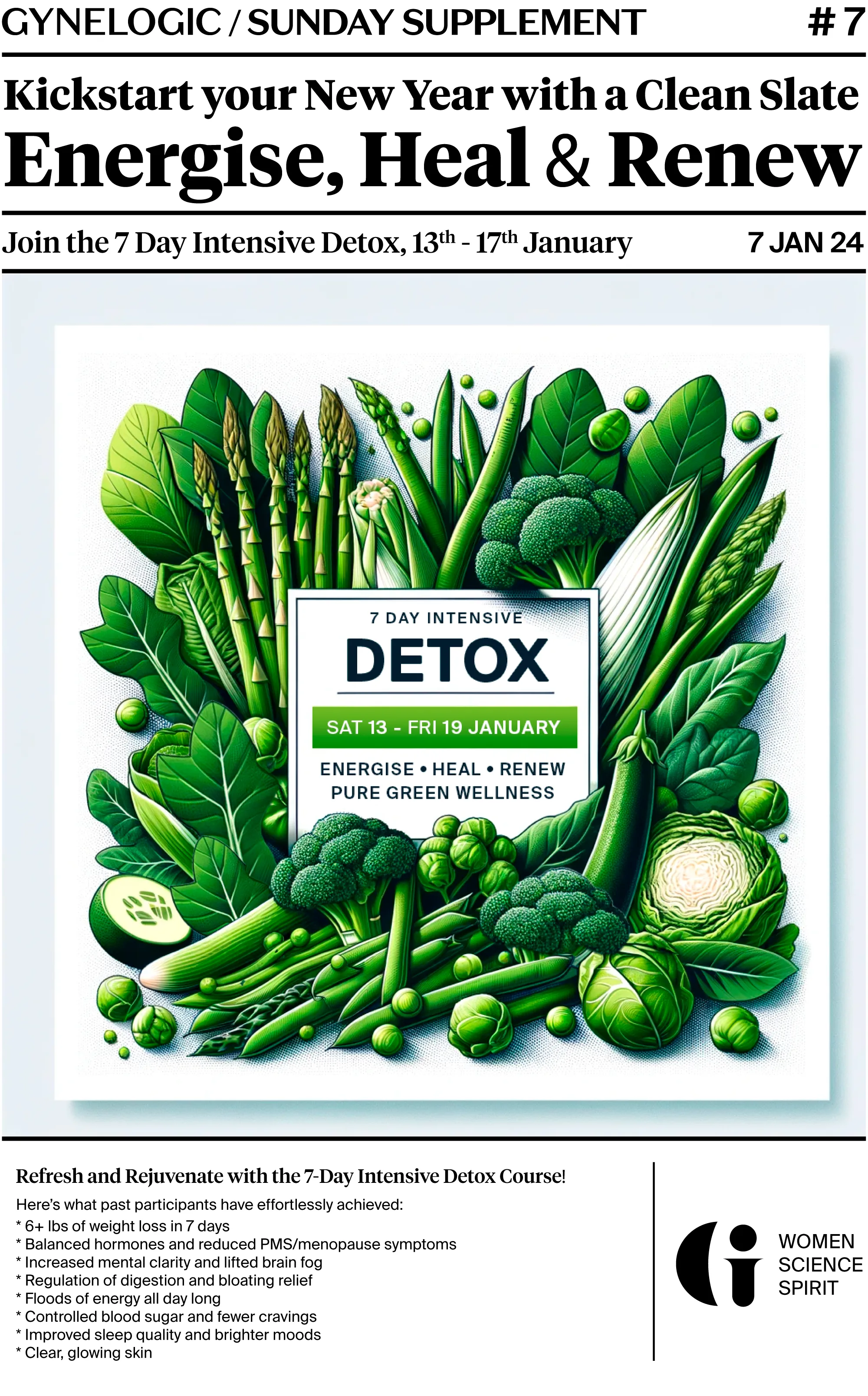

My approach to Managing Endometriosis – A pain-free Life is Possible

The biggest breakthroughs in the management of endometriosis has come studies showing that nutrition, detoxification and supplements can effectively and significantly reduce pain and inflammation.

Nutrition

While there is no one-size-fits-all diet for endometriosis, there are certain foods that can exacerbate inflammation and make symptoms worse, and others that can help reduce inflammation and promote healing.

As an oestrogen-driven condition, nutrition has to focus on preventing excess oestrogen and other hormone intake. For this reason I recommend:

- avoiding red meat and focusing on seafood for protein. Protein is important for tissue repair and hormone balance, but it’s important to choose lean sources to avoid excess saturated fat. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish like salmon and sardines can help reduce inflammation and promote hormonal balance. A diet high in fish and seafood is ideal for endometriosis.

- avoiding cow’s dairy

- avoiding soya

- avoiding high sugar foods. High sugar drives insulin which can increase oestrogen.

For lowering inflammation I recommend:

- avoiding gluten and all grains

- avoiding all processed foods. These are often high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats, which can exacerbate inflammation and worsen symptoms.

- avoiding artificial sweeteners, which disturb the gut microbiome.

- avoiding pro-inflammatory seed oils like sunflower oil and focusing on monounsaturated fats, found in foods like avocado and olive oil.

- avoiding coffee. Caffeine can worsen symptoms, so it may be worth experimenting with avoiding or reducing this to see if it helps.

- include vegetables with every meal. These are rich in fibre, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, which can help reduce inflammation and promote healing. Choose a variety of colourful fruits and vegetables, including leafy greens, berries, citrus fruits, and cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts.

Include plants that help to detoxify oestrogen via the liver:

- Artichoke hearts

- Bok choy

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Cabbage

- Cauliflower

- Greens: beet greens, kale, chard, collard, mustard greens and rocket

- Onions, garlic, and scallions

- Oregano

- Rosemary

- Sage

- Thyme

Gut and Vaginal Microbiome Restoration, and Detoxification

- Healing intestinal and vaginal microbiome imbalance and supporting liver detoxification restores hormone balance and remove sources of inflammation.

Supplements

- The nutrients discussed above support hormone metabolism and reduce inflammation, but I just want to note that 4 supplements have made the most difference in my clinical experience: vitamin E, vitamin D, NAC and methylated B complex in high doses.

- In a 2017 study a cohort of endometriosis patients was treated for three months with a composition including quercetin, curcumin, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate and omega 3/6 displayed a significant reduction of the symptoms at the end of the treatment:

- headache from 14% to 4%

- cystitis from 12% to 2%

- muscle aches from 4% to 1%

- irritable colon from 15% to 6%

- period pain from 62% to 18%

- pain with sex from 30% to 15%

- chronic pelvic pain from 62% to 18%

- PGE2 from 3404ng/l to 137 ng/l

- CA-125 from 61.4 U/ml to 38 U/ml

- 17 Beta Estradiol on day 21 of the cycle from 184pg/ml to 171 pg/ml.

Lifestyle

- For detailed lifestyle approaches (and additional discussion) please enrol on my free course, Endometriosis Explained

Takeaways

Endometriosis is a complex condition that involves immune dysregulation, inflammation, gut and microbiome imbalances, and a dominance of local and circulating oestrogen.

- Endometriosis most likely starts with differentiation and migration of any Mullerian tissue during the formation of the embryo resulting in patches of this tissue being laid down in abnormal locations in the pelvis or elsewhere in the body. Later in life, these misplaced patches of tissue develop into endometriosis when they are exposed to oestrogen.

- Silent endometriosis may be a cause of infertility

- The maintenance of endometriosis is largely mediated by prostaglandin E2 which leads to increased growth of lesions and inflammation

- High levels of prolactin mediate pain and can be reduced with dopamine boosters

- Increased risk with chemicals commonly found in plastic and cosmetics.

- Increased risk with imbalanced gut and vaginal microbiomes

- Increased risk with genetic variants of COMT and MTFHR genes

- A hormone balancing diet is essential

- Multiple supplements are supportive in prevention and treatment particularly vitamin E, NAC, vitamin D and methylated B vitamins